There’s a scene in Homer’s Iliad (Book 11) in the front

of my mind. The scene describes a significant turn in battle. Here’s the short

version: Agamemnon has spent nearly ten years in siege against the city of Troy

(the purpose and outcome are not the point of discussion here). The

scene-in-mind describes the Trojan Hector in battle and what captures my

attention is that which holds his attention. While the battle is raging, Hector

watches Agamemnon. When the King Agamemnon is fighting with his men on the

front, Hector keeps back but encourages his men in the melee; but, when

Agamemnon mounts his chariot, Hector steps into battle and fights until at last

the Trojans drive Agamemnon and his armies back to their ships. Hector is not

distracted by the particulars of the battle. Instead his eye is fixed on the leader

of his enemy. When Agamemnon is no longer the strength of his troops, Hector

steps in and drives the invaders away from the city.

This ancient scene comes to mind as I ponder opening

questions asked at the beginning of Tony Evans’ “Kingdom Man” Bible study. We

are given this statistic: “roughly 70 percent of all prisoners come from

fatherless homes. Approximately 80 percent of all rapists come from fatherless

homes.” Then there comes the question: “are these statistics surprising? Why or

why not?” (Caveat: I suffer from over-thinkage, so brace yourself).

My reflex action is to say, “yes” but I must honestly

say “no,” this statistic does not surprise me. My reaction to the statistic is

not “surprise.” I am not comfortable having an emotion suggested to me and I

had to honestly search to determine how I really feel. At last I have found my

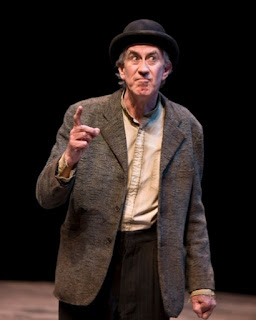

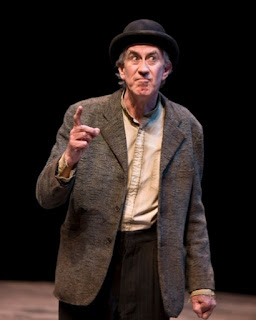

word. I am not “surprised” but I am “appalled” [I hear the voice of Barry

McGovern acting as Vladimir in Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot” as he

growls out the depth of his new-found emotion (for which he, too had to search).

“AP-ALLED!”]

Why am I appalled? The problem addressed is not so

much that men are in prison, nor is it that a percentage of those men are

rapists that have come from fatherless homes. The problem that causes me to

pale is this: there are males not in prison who don’t have the fortitude to

stand up and speak truth, doing everything possible to help others stay out of

there.

The real issue, the real battle is not on the front

line. Consider first the source of “fatherlessness” and who steps in to fill the

void. Evans’ discussion on fatherlessness presents only two options: the father

1) who has walked away with no sense of obligation or responsibility; or, 2) who

has made himself unavailable, unapproachable. Novelist Donald Barthelme gives

us an idea of what happens within the child who at some point searches out the

source of his confused anger:

“He is mad about being small when you were big, but

no, that’s not it, he is mad about being helpless when you were powerful, but

no not that either, he is mad about being contingent when you were necessary,

not quite it, he is insane because when he loved you, you didn’t notice.” (The

Dead Father)

What about the third option (and I suggest this not

as criticism, but as an observation): what about those families who lost their

father due to death?

Further, what about fatherless children who turned

out ok, those that are not in prison and/or are not rapists?

Here is where I find myself appalled: I along with

so many others permit these statistics, allow them to occur. I along with so

many others know what young men need to hear and know in order to 1) help them

be good earthly citizens; and 2) become heavenly citizens. I am appalled

because I let this happen. Both Hector and Agamemnon give me something to

consider: I must never leave the front lines where the battle rages against a

real enemy (don’t ask me where Menelaus was, Agamemnon’s brother). Also, I must

keep my eyes open, ready to step in and fill the gap or someone else will.

Having said this, I find God’s words both comforting

and disturbing: “I searched for a man among them who would repair the wall and

stand in the gap before Me on behalf of the land so that I might not destroy

it, but I found no one.” (Ezekiel 22:30).

God is looking for men to fill a gap. Defenses are

compromised and the city of Mansoul is in jeopardy. We must fill in the gap as

representatives of the King. This means when men go wrong, we must tell them of

their wrong based on the standards of the King. We must also point them to the way

of reconciliation to the King.

My reflex action is to say, “yes” but I must honestly

say “no,” this statistic does not surprise me. My reaction to the statistic is

not “surprise.” I am not comfortable having an emotion suggested to me and I

had to honestly search to determine how I really feel. At last I have found my

word. I am not “surprised” but I am “appalled” [I hear the voice of Barry

McGovern acting as Vladimir in Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot” as he

growls out the depth of his new-found emotion (for which he, too had to search).

“AP-ALLED!”]

My reflex action is to say, “yes” but I must honestly

say “no,” this statistic does not surprise me. My reaction to the statistic is

not “surprise.” I am not comfortable having an emotion suggested to me and I

had to honestly search to determine how I really feel. At last I have found my

word. I am not “surprised” but I am “appalled” [I hear the voice of Barry

McGovern acting as Vladimir in Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot” as he

growls out the depth of his new-found emotion (for which he, too had to search).

“AP-ALLED!”]